LA PLUS

BELLE DES

CAN

Past exhibition

Emeka Ogboh

”ABJ” preview

Paris Internationale 2023.

Set design Clémence Farrell

Video display ETC ONLYVIEW

Films Barbara John Production

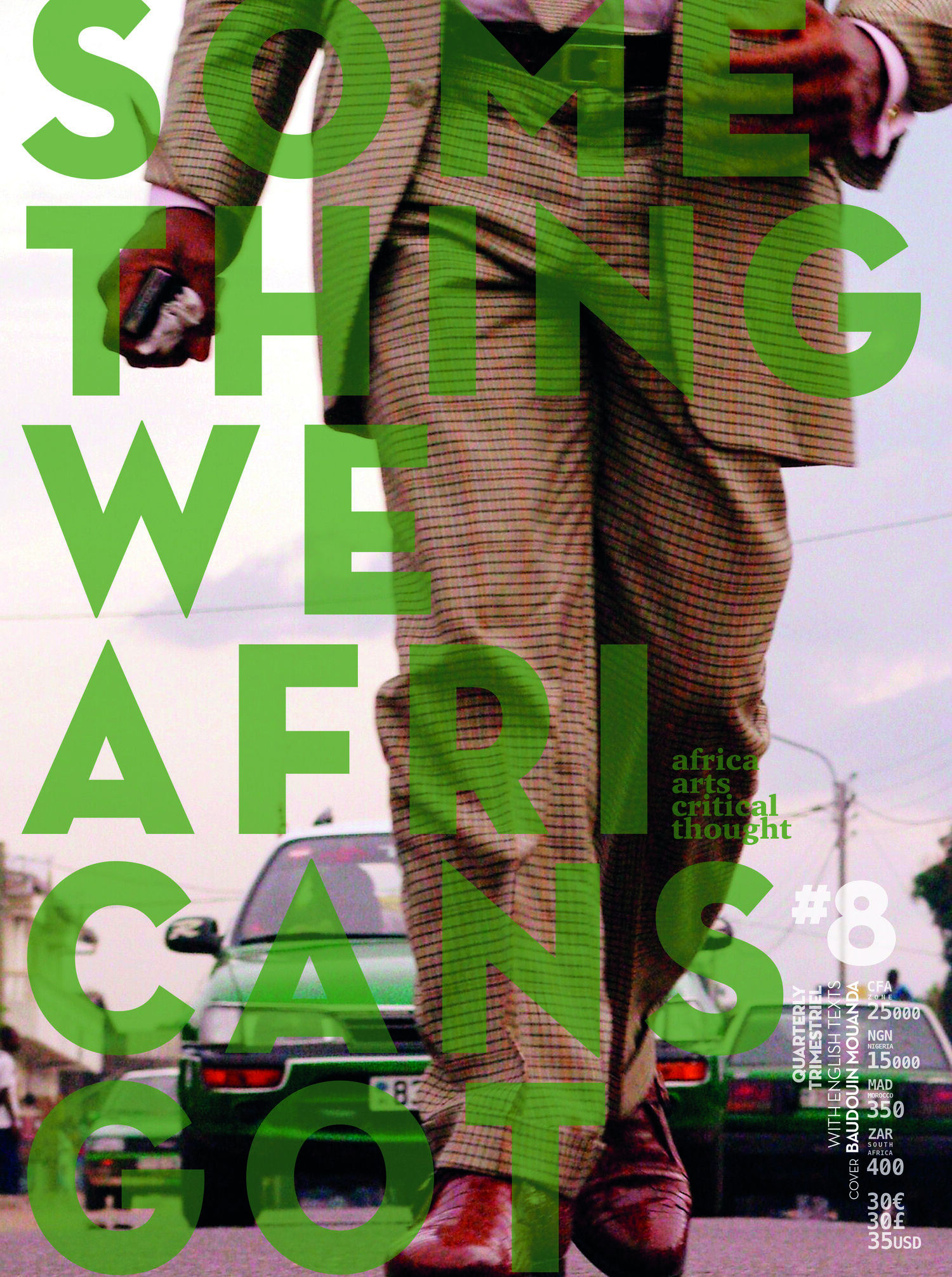

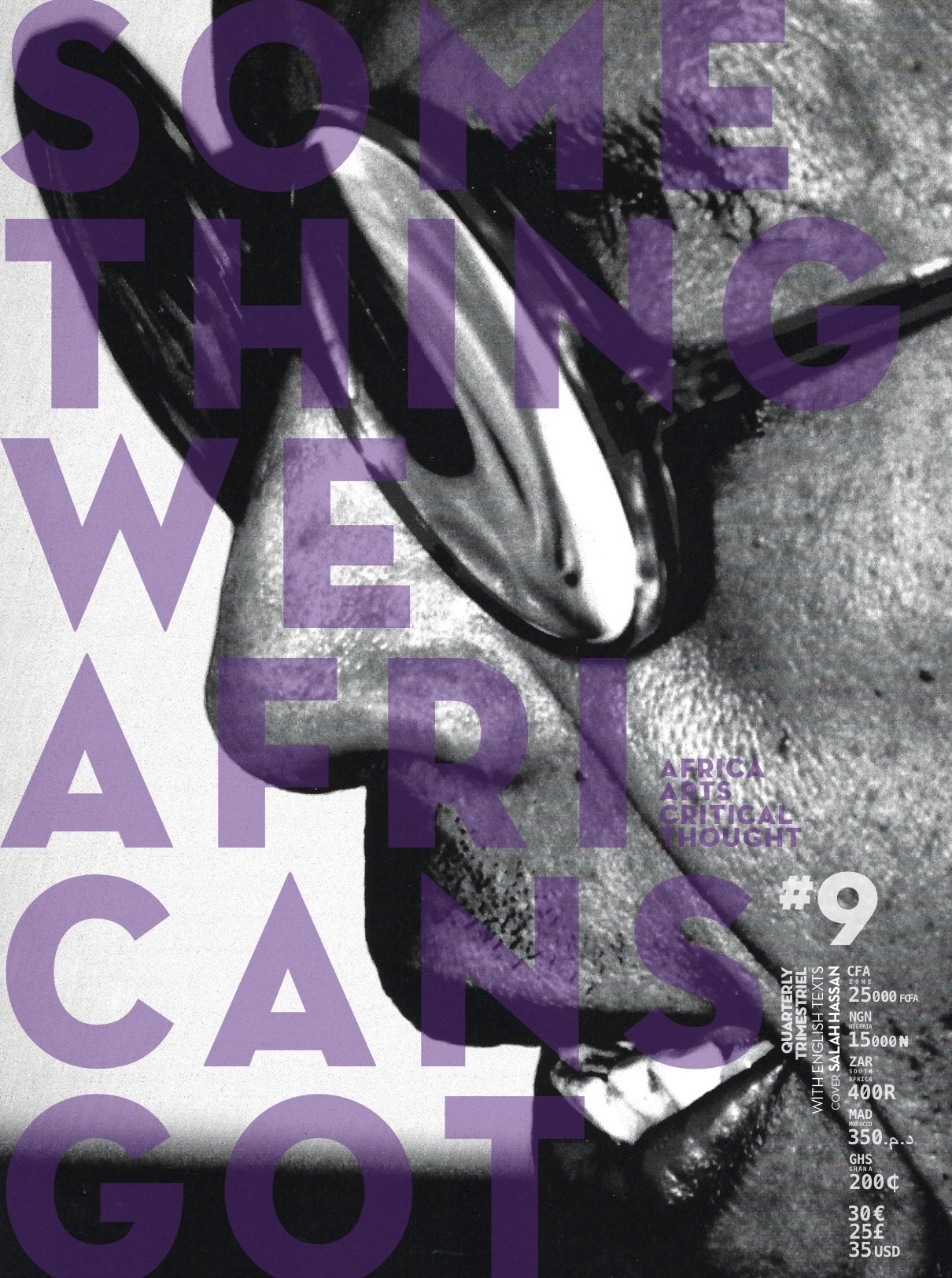

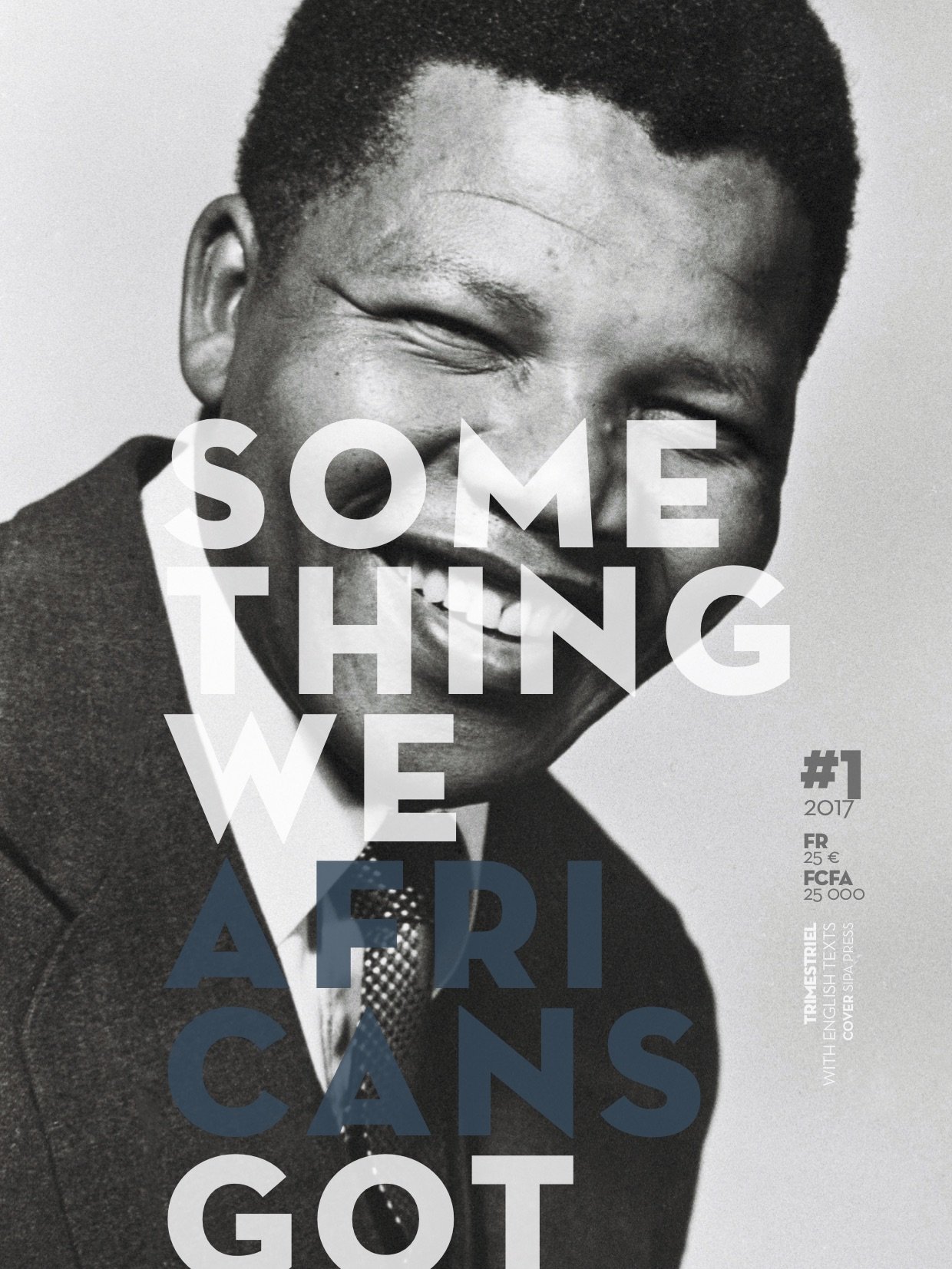

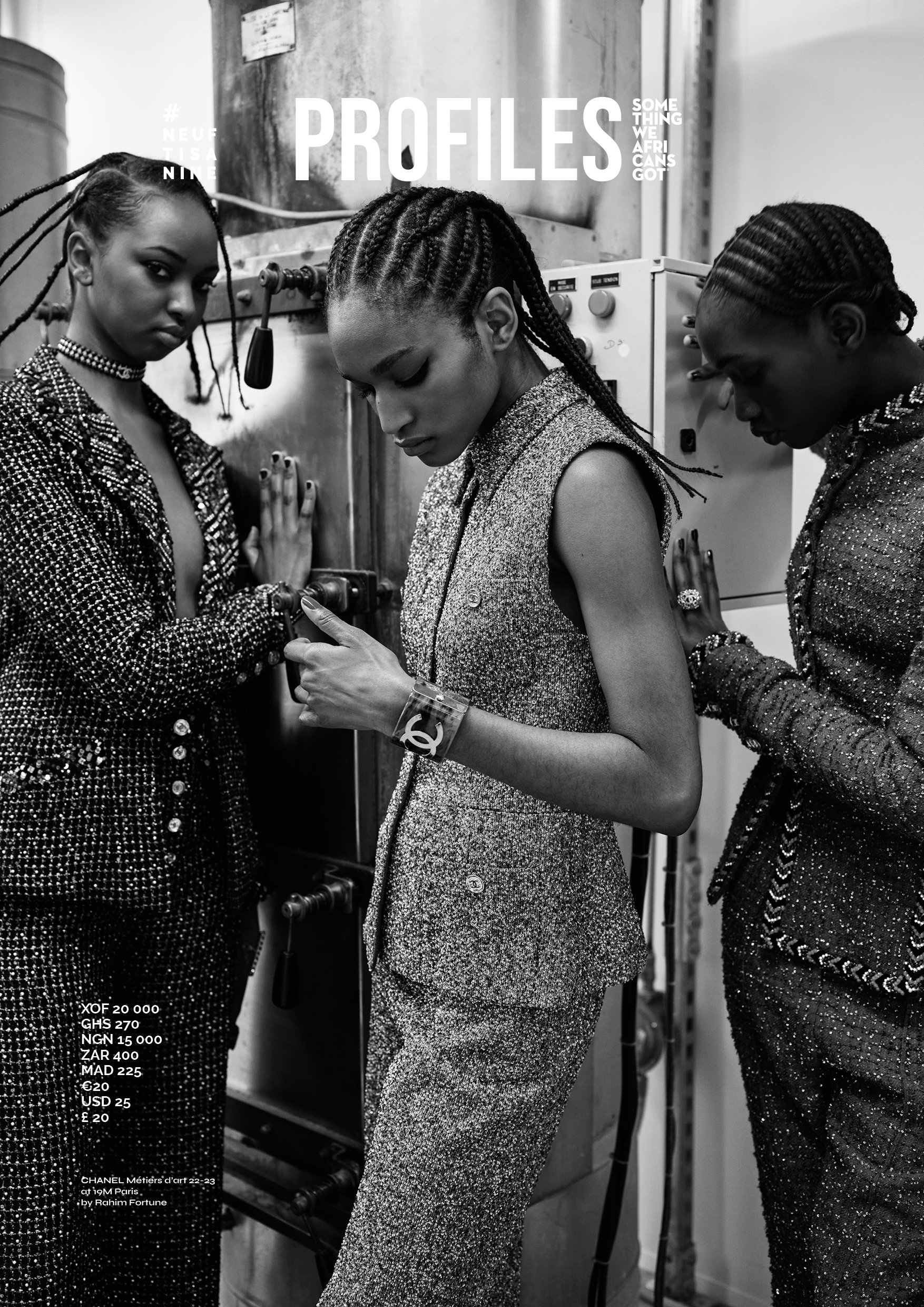

SOMETHING art space +

Goethe Institut Abidjan

Oct 17th-22nd

Venue

Paris Internationale

Emeka Ogboh

Emeka Ogboh

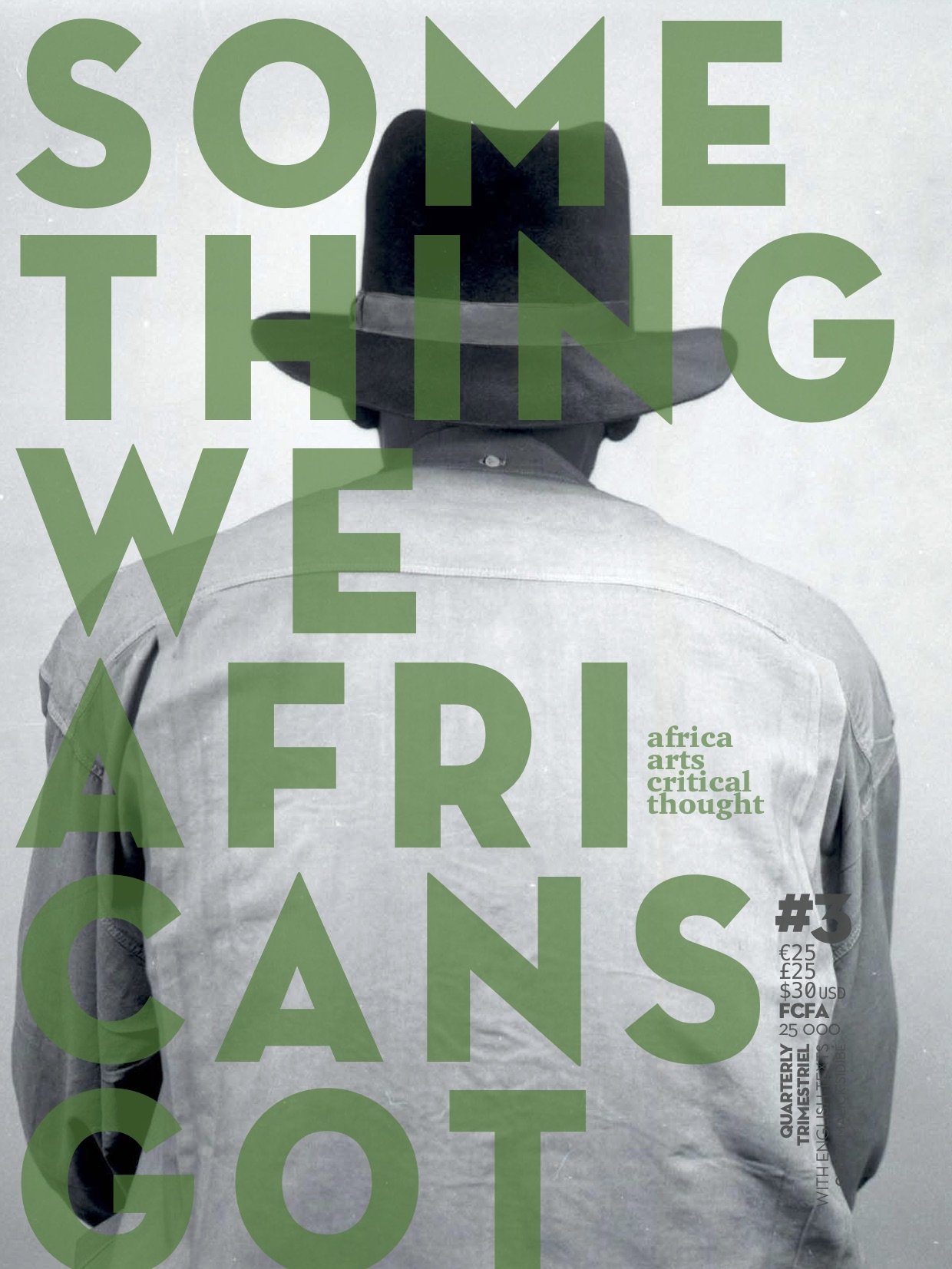

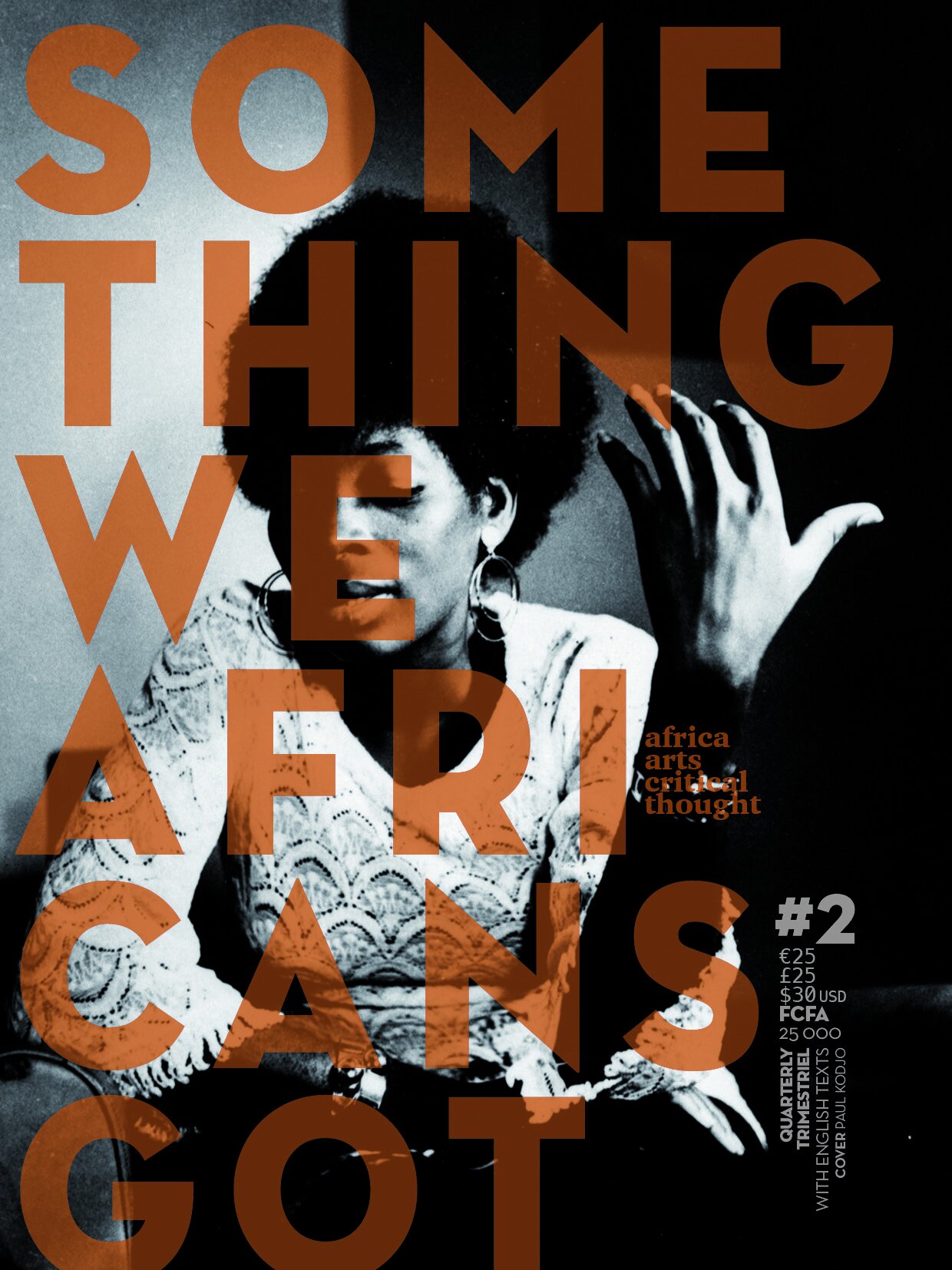

SOMETHING

January 2024

Venue

SOMETHING, Abidjan

The piece presented at Paris Internationale edition 9, is an 25 minutes excerpt from a 1 hour work that will be shown in January 2024 at SOMETHING Abidjan

With the support of ETC onlyview and Agence Clémence Farrell. Special thanks to Galerie Imane Farès.

Emeka Ogboh engages with places by using all five human senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. His art installations and culinary creations incorporate sensory elements to explore how private, public, collective memories and histories are translated, transformed, and encoded into different sensorial experiences. Ogboh’s works delve into how sensory perceptions capture our connections to the world, shape our comprehension of reality, and offer a backdrop for examining critical issues such as migration, globalization, and post-colonialism.

The project “ ABJ ” aims to reveal the rich culture and daily life of the city’s residents through the lens of migration. The bustling markets of Abidjan, where people from all over Côte d’Ivoire and West Africa come to trade goods and interact, are particularly intriguing and offer a unique experience for this project.

The most compelling way to document the unique atmosphere of these markets is through sound and film. The multiplicity of languages, the sounds of vendors selling their goods, the haggling of customers, and the bustle of people moving through the market all contribute to the lively ambience; the markets are a melting pot of cultures, languages, and traditions.

To showcase these findings, an immersive, multichannel installation of sound and video will be created, allowing visitors to step into the heart of the market and be transported by the sounds of vendors selling their goods, the chatter of customers haggling over prices, and the bustle of people moving through the space. The installation will feature a multi-channel sound design and interactive elements that allow visitors to explore the market interactively.

about video art

“ In the fall of 2018, while in London for a conference, I crossed the city to see UUmwelt, the new installation by Pierre Hughe (b. 1962) at the Serpentine Galleries, anticipating an eye-opening prod from this singular artist. For several decades, I have appreciated how he challenges viewers with well-researched, timely subjects that he transposes into a finely tuned composition -and UUmwelt did not disappoint.

It brought me face-to-face with enigmatic, vaguely figurative images shown on imposing LED screens. My movement through the galleries caused slight shifts in the forms; I imagined one shape to be an odd prehistoric animal, another an abandoned car. Each was situated in a desolate, desert-like landscape.

Reading about the project, I learned that Hughe had created the images using the brain waves of someone who had been asked to imagine a situation, in an informatics lab in Japan. In other words, Hughe had managed to capture the entities straight from the inner machinations of the human brain. What would have seemed far-fetched and unfeasible forty years ago has now entered the realm of possibility.

Hughe’s installation is evidence that the urge to experiment is as strong as ever, and that the field originally defined as video art has slowly, radically transformed to encompass a far wider range of technological explorations in art–moving from fringe to mainstream during the period that began when I landed my first position, a research post, at the Museum of Modern Art, in late 1970. The innovations of trailblazing artists like Hughe are what have kept my mind nimble throughout a long and rewarding career as a curator, writer, and professor.

The story of video art begins as video gear first reached the consumer market in the mid-1960s, when much of the world seemed to be in radical transition. The time was right.

We thrived in the “now,” adapting Polaroid’s instant photograph, the xerographic photocopy, and the telephone answering machine to art and everyday life. We busily recorded and exchanged cheap audiocassettes with favorite playlists of the latest music. David Bowie’s song “Space Oddity” moved up the pop charts in 1969, the same year that two US astronauts drifted out of Apollo 11 and walked on the moon. With the aid of technology, humans seemed capable of anything. At the same time, 1960s counterculture instigated alternatives to social norms, with its free love and free speech and the increasing prevalence of meditation and mind-bending drugs that torqued the individual’s perceptions and imagination. Out of this environment, video art burgeoned from the grass roots.It began with the portable camera, the monitor, and black-and-white videotape-the long, narrow strip of plastic with a thin, magnetizable coating that contains the image and/or sound. During recording and editing, video was visible on a monitor screen and audible through a sound system or headphones. It was easily replayed, copied, broadcast live or later from a tape, and today is streamed. I fell in love with the newly accessible medium and worked hard to learn whatever I could.

VIDEO / ART. The first fifty years describes the madcap trajectory of a pliable medium, as video opened up and became a multifaceted art form that grew to encompass a range of formats, including not only single-channel videos but also multi-screen installations and projections; immersive audiovisual environments (sometimes incorporating interactive components); and moving-image works that are streamable as digital files. The field has moved in from the periphery of the art world and has morphed into the more expansive category of media art, defined by the quality of being dependent on technological components to function. This account of how video became simply art follows my own journey as a proponent of its progress.”